Researcher-Expert Collaboration and the Involvement of Education Researchers in the Making of Education Policy

Guy Tchibozo

LISEC UR 2310, Université de Strasbourg, France

Education Thinking, ISSN 2778-777X – Volume 2, Issue 1 – 2022, pp. 19–39. Date of publication: 22 April 2022.

Cite: Tchibozo, G. (2022). Researcher-Expert Collaboration and the Involvement of Education Researchers in the Making of Education Policy. Education Thinking, 2(1), 19–39. https://analytrics.org/article/researcher-expert-collaboration-and-the-involvement-of-education-researchers-in-the-making-of-education-policy/

Declaration of interests: The author has no interests to declare.

Author‘s note: Guy Tchibozo is a member of LISEC, the education research centre at Strasbourg University, France. His research focus is on education policy and vocational education and training. (ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5865-7900, http://www.lisec-recherche.eu/membre/tchibozo-guy, 01.tchibozo@gmail.com, https://gtsite.xyz/1/)

Copyright notice: The author of this article retains all his rights as protected by copyright laws.

However, sharing this article – although not in adapted form and not for commercial purposes – is permitted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial–NoDerivatives BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license, provided that the article’s reference (including author name(s) and Education Thinking) is cited.

Journal’s area of research addressed by the article: 19-Education Policy

Abstract

Compared to what can be seen in such other public policy sectors as health or economy, researchers’ involvement in policymaking is less frequent in education. Given that policymaking is a collaborative process, this article explores how the collaboration rules, as well as differences in professional personalities and cultures among players, may trigger education researchers’ comparatively lesser involvement in the making of education policy. The article focuses on the collaboration between researchers and experts. Based on an analytical framework, an international survey of researchers and experts (N=114) with experience in collaboration in education policy making was conducted. Quantitative analysis (simple descriptive statistics and independence tests) of the data was carried out. The results show that the education researchers who participate in policy-making workgroups may find themselves faced with governance and knowledge-sharing rules they are not accustomed to, unmet expectations, and conflicts. It also appears that education researchers have professional personalities and cultures that significantly contrast with those of experts. It is suggested that such challenges and differences may generate both exclusion and self-exclusion of many education researchers from the making of education policy. More openness and professional changes are called for.

Keywords

Education policy, Experts, Policy involvement, Researcher-expert collaboration, Researcher personality

A well-established practice in disciplines such as physics, medicine, or economics, the involvement of researchers in the making of public policy in their area of specialty is much less so in education (Burkhardt 2019). Reasons for this lie – according to Burkhardt – in education research communities’ preferences for: (a) emphasising differences in views to stand out from others, but thus obstructing strong disciplinary consensus that policymakers would not have been in a position to lightly overlook while considering policy options; (b) speculative thinking inherited from the humanities tradition, which ignores the use of modelling, empirical tests, replications of experiments, and opposes the search for “solutions”, “treatments”, and “tools”, yet a major expectation of policymakers; and (c) individual visibility, which leads to abdicating large team research, although a better way towards broad-based results, more relevant to guide public policy. Burkhardt points out that such preferences make education research inaudible to policymakers because it is seen as lacking authority, credibility, and general relevance, so that they can then pretend to do without it.

Other authors (Stone et al., 2001) emphasise the reserve of policymakers towards researchers, seen as too often prone to propose “radical questionings”, “paradigm shifts”, and “innovations”, each more “unrealistic” and “costly” than the next.

More generally addressing the influence deficit of education research in the policy field, Gale (2006) adds to the above education research imbalance between over-analysing the nature of policy and blatantly disregarding how to influence policies. Gale (2006) as well as Ion and Iucu (2015) also point to the “inaccessible” language of education research works. Smith et al. (2021) show how mismatches in timeframes, temporality, and timings may jeopardise long-term persistence in interactions between education researchers and policy players, while the quick pace and time unavailability inherent to policy actions may not allow researchers to develop the proper research needed.

This article explores alternative reasons for the comparatively lesser involvement of education science researchers (hereafter “education researchers”) in the making of public education policy. Adopting a distinctive under-researched angle, the approach focuses on the very nature of the involvement process, and in particular its collaborative dimension. Involving in policymaking entails collaborating with other policy players (see for example Smith et al., 2021) who, from the perspective of a researcher, are in the first place the education policy experts (hereafter “experts”). Therefore, collaboration between researchers and experts is at the core of this approach.

What is at stake in this research is a deeper understanding of the hindrances to education researchers’ involvement in education policy making, a key condition for better promoting research-informed education policy and further developing, guiding, and supporting research-based education practice.

The remainder of this article is organised as follows. First, the analytical framework is introduced. Next, the method for data collection and analysis is explained. The study sample is then described. Finally, the results are presented, and conclusions are drawn.

Analytical Framework

Analysing the “collaboration” between “researchers” and “experts” requires first defining how each of these three words is to be understood in this research.

Researchers are defined as those people who carry out research meant as a specific process aimed to create new knowledge. In this process, researchers first review the existing knowledge base on the issue of interest, so as to be able to make the most of it, with the aim to enrich it, and not just compile, repeat, or paraphrase already existing knowledge. Researchers are then supposed to set up analytical frameworks within which their views and reasonings are to be constructed and understood, and their results interpreted. Researchers are expected to make explicit their analysis methods. Both this objective and this process are what define the research work. Instead, although research may certainly in many cases help solve problems that society is faced with, solving (or attempting to solve) these problems are in no way what specifically defines researchers’ work.

In contrast, experts are defined as people whose work aims to mobilise and apply knowledge, skills, and competences to solve or contribute to solving problems. Experts’ work is unbound to any particular approach that would be consubstantial with the role of expert. Obviously, experts’ work may in some cases contribute to creating knowledge, however, this is in no way what defines it.

Collaboration is taken in the most general sense, without distinguishing between simple communication, coordination, cooperation, or partnership, and without prejudging the form, direction, intensity, or stability of the relationships between players. There is researcher-expert collaboration as soon as there is the participation of at least one education researcher and at least one expert in an action contributing to education policy making. Collaborations run subject to functioning rules and develop more or less smoothly. To allow for in-depth analysis of collaborations, categorising the functioning rules and possible tensions and conflicts was necessary.

Functioning Rules

The modalities of researcher-expert collaboration are determined by the functioning rules of the workgroup within which the collaboration takes place. At least three sets of rules need to be considered. Firstly, the rules of governance, which determine the way in which the workgroup is administered. The rules of knowledge transfer, secondly, determine the processes for knowledge transfer among policy-making players and stakeholders. Thirdly, the rules of knowledge utilisation, which determine how and to what extent the transferred knowledge will be translated into policy.

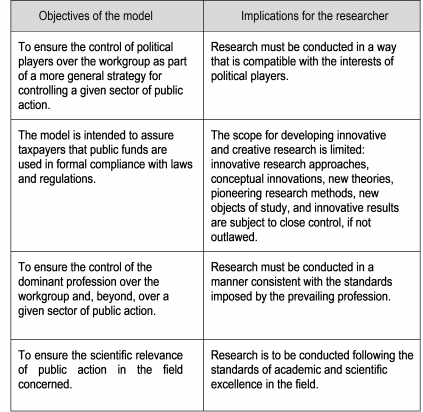

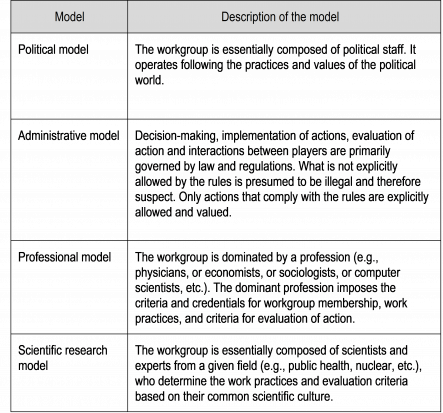

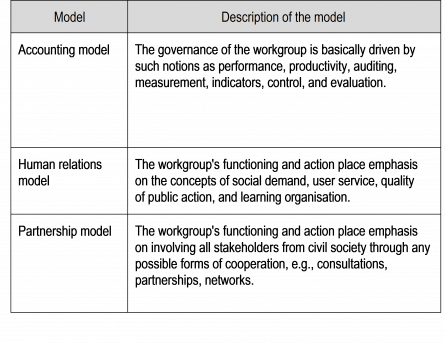

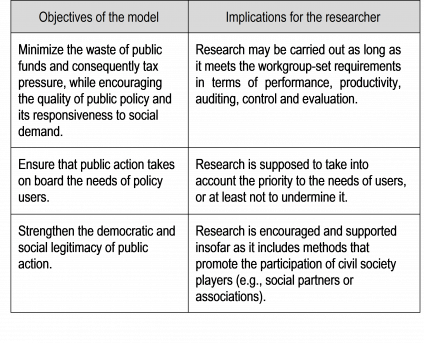

The rules of governance determine the distribution, exercise, and regulation of powers and responsibilities within the workgroup. The literature on public management (e.g., Ferlie & Geraghty, 2005) identifies different governance models. Table 1 presents seven such models that may apply to researcher-expert collaborations.

Table 1.

Seven Workgroup Governance Models That May Apply to Researcher-Expert Collaborations

|

|

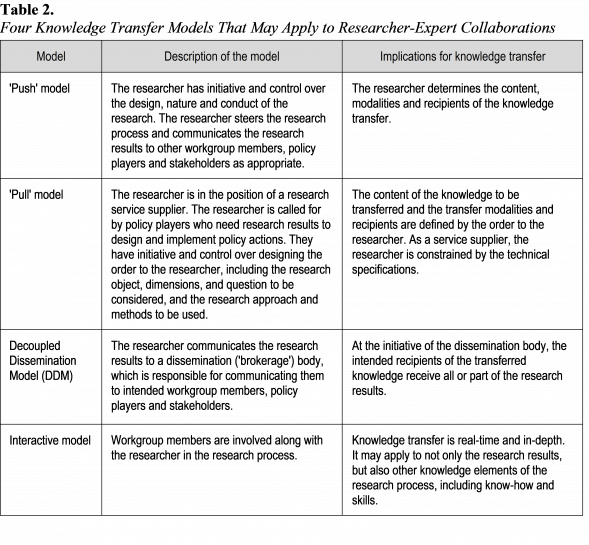

The rules of knowledge transfer influence the way in which the researcher’s knowledge, know-how, and findings will be transferred to other workgroup members, policy players, and stakeholders (transfer to the scientific community at large and to the general public is not the point here, the focus being on transfer intended for translation into policy). The literature on knowledge transfer (e.g., Terzieva & Morabito, 2016) provides examples of existing practices. Table 2 presents four knowledge transfer models that may apply to researcher-expert collaborations.

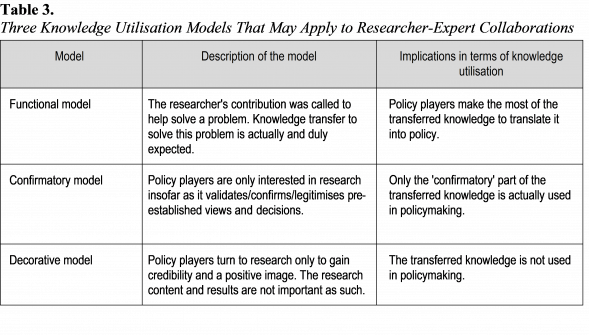

The knowledge utilisation model determines the extent to which the transferred knowledge will actually be translated into policy. The literature on knowledge utilisation (e.g., Estabrooks et al., 2006; Ion et al., 2019; Weiss, 1979) suggests that translation into policy may either occur spontaneously following a process of knowledge accumulation (“enlightenment”) or be beset with political and bureaucratic obstacles and hence require purposeful strategies. Table 3 presents three knowledge utilisation models that may apply to researcher-expert collaborations.

Tensions and Conflicts

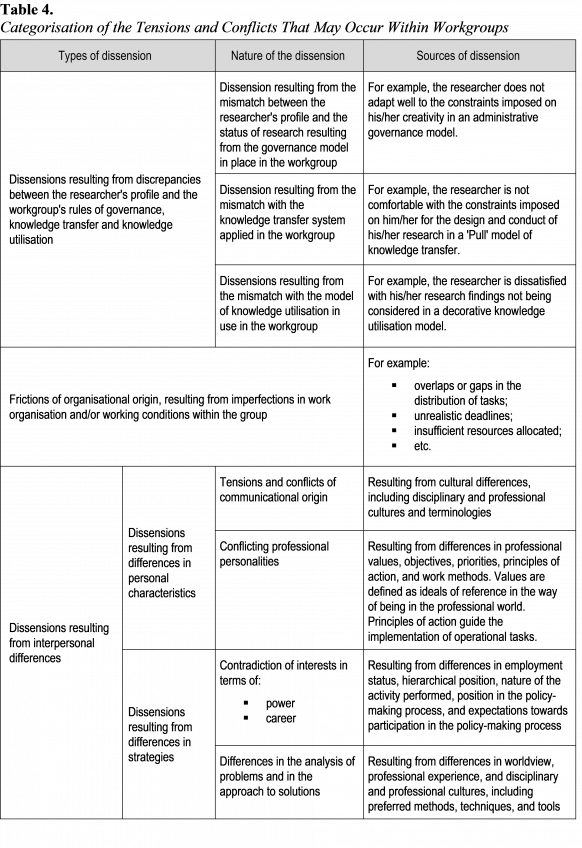

One cannot expect the professional personality, representations, and expectations of a researcher who joins a workgroup to adjust spontaneously and smoothly to the functioning rules of the group. Tensions and conflicts may arise. Even if the researcher’s profile would adjust to the functioning rules, interactions between group members are other possible sources of tensions and conflicts. Tension and conflict are to be understood here as the respective expressions of the minimum (tension) and maximum (conflict) intensity of dissensions on a continuum. Many theories, originating in sociology, psychosociology, or social psychology, offer insights for categorising conflicts. However, as the categories to be set here were also intended to guide respondents at the questionnaire survey stage, an alternative approach was preferred, focused on practical criteria likely to reduce any risks of ambiguity or misunderstanding in the minds of international respondents with a variety of disciplinary backgrounds (Table 4).

The management of tensions and conflicts may resort to one of two paradigms: either management by the parties or institutional management. The main categories of these paradigms identified in the literature were used. The literature on parties’ management of individual work conflicts (social conflicts are not the point here) basically highlights five types of approaches coined by Blake & Mouton (1964) and Thomas (1976, 1992), i.e., “avoiding”, “accommodating”, “compromising”, “collaborating”, and “competing”. The literature on institutional management (e.g., Goldman et al., 2008; Olson-Buchanan & Boswell, 2008) specifies a range of ways (some of which combinable) including resorting to a decision by the hierarchy; referring to a standing institutional dispute resolution mechanism; appointing a neutral third-party responsible for re-establishing communication between protagonists (mediation) or bringing about a solution (conciliation, arbitration); and taking legal action.

Method

The data analysed in this article come from a sample of researchers and experts with experience of researcher-expert collaboration in the construction of education policies, at local, regional, national, or international level. To constitute this sample, probability sampling could not be used as it does not exist any sampling frame for this population. Neither could a

representative sample be composed as the characteristics of the parent population are unknown. Convenience sampling and self-selection sampling were therefore used. It was thus expected to capture aspects of actual collaborations, even though their prevalence in the parent population may not then be inferred.

In practical terms, posts informing on the survey, with a link to the questionnaire, were placed on the websites of education research centres. Invitation emails were also sent to researchers and experts worldwide, at their professional addresses available on the websites of their universities or international organisations. Any available email address was used, no prior selection was made. Both university departments and faculties as well as education research centres and international organisations likely to have an interest in education policies were targeted.

The questionnaire was anonymous and self-administered online. The respondents were requested to position themselves as researchers or experts, and were to that end provided with definitions based on the analytical framework. Based on the categories from the analytical framework, they were asked to specify the types of collaboration they participated in and describe their collaboration experiences.

The data collection phase run from January to March 2019. Eight hundred people responded to the questionnaire, but mostly in part only, for example, with just the socio-demographic information section (gender, age…) completed. Hundreds of responses thus turned out to be useless with respect to the survey topic and were therefore discarded. Lots of responses were also discarded upon scrutiny to minimise the risk of bias, for example, fantasy responses and multi-participations (IP control had been deactivated on the survey platform to enable several respondents from the same institution to use the same computer). Only 99 researchers and 15 experts provided sufficiently complete, usable, and trustworthy responses. So, only these 114 respondents were kept as composing the study sample.

The data collected were analysed using simple descriptive statistics and independence tests. The most usual independence test, the chi-square test, could not be used because a major condition for applying it (at least five cases in each cell of the theoretical contingency table) was not met. Three alternative independence tests were therefore used: Fisher’s exact test, Wilks’s G-squared test, and Monte Carlo simulation test.

Sample Description

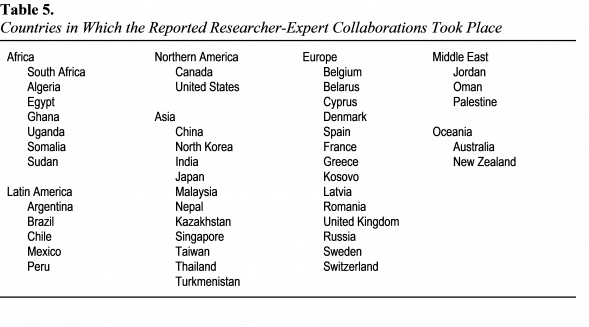

The data collected cover collaborations in 44 countries on five continents (Table 5).

The reported actions have a variety of objectives: pedagogical innovation; administration, development, and evaluation of educational institutions; educating for health, multiculturalism, protecting the environment, and sustainable development; promoting inclusive education and adult education, and fighting illiteracy; strengthening school-business partnerships, inter-university cooperation, and the research capacities of universities; and further involving media in educating the general public.

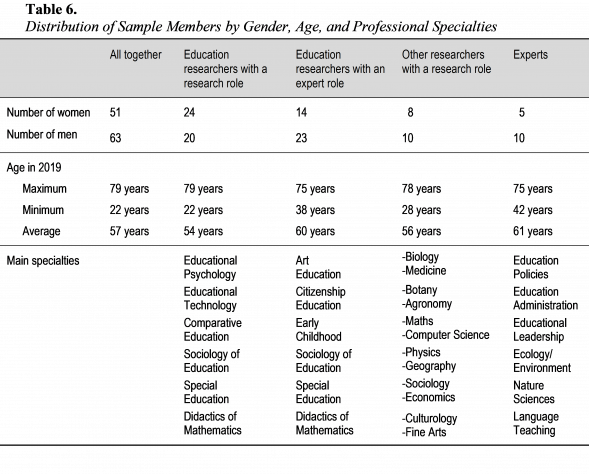

The sample consists of experts and researchers, the latter divided into three groups, differentiated based on their disciplinary specialties and missions in the workgroup:

– education researchers entrusted with a research role;

– education researchers entrusted with expert tasks (e.g., administration, organisation, coordination, advice, evaluation, training);

– researchers from disciplines other than education also entrusted with a research role.

The researchers worked under various employment statuses including short-term and open-ended contracts; research agreements between the home organisation and the host institution; research grants; and volunteering.

More than half of the respondents (51.75%) were at least 60 years old at the time of the survey. Most of the respondents’ answers, therefore, draw on a long experience (sometimes more than 25 years) of researcher-expert collaborations. Table 6 presents the distribution of the sampled researchers and experts by gender, age, and professional specialties.

Results

Four major aspects emerge as potential disincentives for education researchers to involve in education policy making: functioning rules researchers may not be accustomed to, unmet expectations, conflicts, and player differences in terms of professional personalities and cultures.

Governance, Knowledge Transfer, and Knowledge Utilisation Models at Odds with Academic Standards

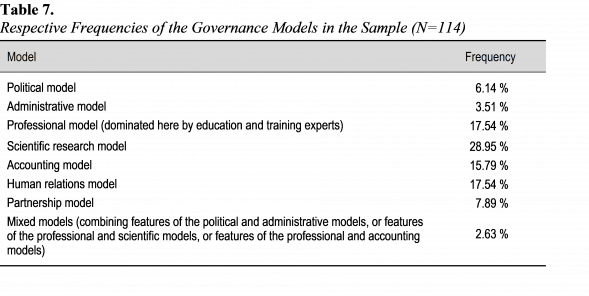

In more than two-thirds of the cases reported in the sample, the rules of governance – which shape the design and conduct of the research activity – diverge from those of the “scientific research” model (Table 7).

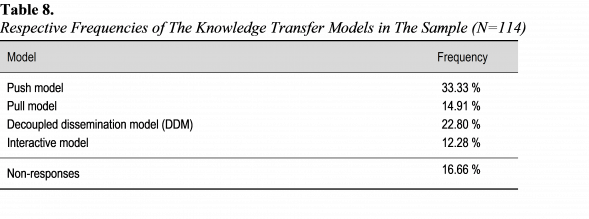

In addition, in only one-third of cases does the researcher have full control over the knowledge transfer process (Table 8).

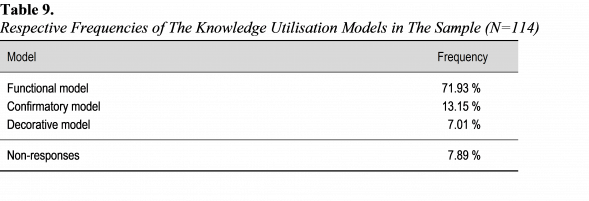

Regarding the translation of the transferred knowledge into policy, the functional model is by far the most frequently cited, but at least 20% of the responses report cases of confirmatory and decorative models (Table 9).

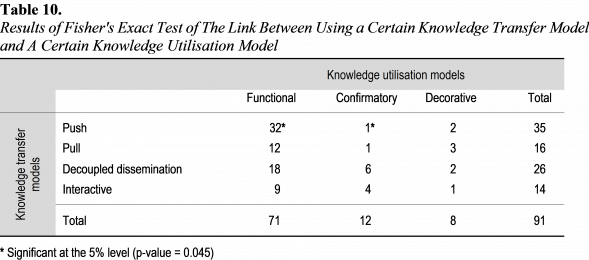

The sample data suggests that the knowledge utilisation model employed by a workgroup is linked in a certain way to the knowledge transfer model of the group. As shown in Table 10, using the Push transfer model is significantly associated with using the Functional utilisation model, and significantly not associated with using the Confirmatory model. No significant link appears between using the Pull, DDM, or Interactive models on the one hand, and using the Functional utilisation model on the other hand. As the Push transfer model is used in only one-third of cases, only in these cases do researchers have some confidence that their results will be considered for translation into policy.

Unmet Expectations

The education researchers report that prior to experiencing collaboration with experts, they were well-disposed and open-minded towards collaborating in policymaking. They had positive representations and optimistic expectations. Certainly do some of them report having had feelings of “curiosity” or even “caution”, “questioning”, and “mistrust”, presuming that their role might be just advisory and not decisional, and concerned about possible political pressure, the challenge of differences in professional and methodological cultures, and the burden of hierarchy and bureaucracy. However, most say they anticipated a positive experience. They viewed the collaboration as an opportunity for policy players to benefit from insights that would help make policy action “more relevant” and “more effective”. They thought they would “contribute to the public good”, and in return, acquire new knowledge, learn new methods, and “move from multi-disciplinary to trans-disciplinary views”. They thus anticipated “fluid”, “collegial”, “mutually respectful” collaborations, “grounded on evidence, knowledge, and research”, and in which a clear awareness of mutual benefits would encourage all players to overcome possible prejudices and obstacles. They expected to “be welcomed” and even to “enjoy” the collaboration.

The overall tone of the post-experience assessment is clearly disenchanted. Some respondents acknowledged that they had actually been able to publish and conduct expert functions, “better understood the importance of applied research” and policy-making processes, “had an enriching experience of interdisciplinarity”, and even witnessed cases of “policy actions taking onboard research results”. These expressed the feeling of having been “useful to society”. But most respondents emphasised instead the difficulties and disappointments they have been through. Overcoming disciplinary boundaries proved to be much more demanding than expected: “The world of research is not very close to that of experts … A common language must be built before cooperation can take place”; “cultural and methodological barriers persist”; “collaboration needs to be prepared; its success requires time to build relationships and negotiate”. Many said that the expected collegiality and openness didn’t show up. Some respondents perceived research as having basically served as an “alibi” to legitimise pre-decided directions, since the non-confirmatory part of their results has been simply ignored. According to many respondents, their “creative and innovative suggestions” have “failed to overcome the accounting logic”. “Partisan ideology”, “power games”, “personal agendas”, “egos”, and “personal ties” are said to often prevail over “reason”. Some also express reservations about the methodological skills of experts.

Interestingly, several experts expressed disappointment over education researchers failing to provide them with “robust and reliable figures and measurements”. While “some researchers are very good, others do not have the words ‘validity’ and ‘reliability’ in their vocabulary … In many fields of education, the focus on exclusively qualitative approaches limits the potential effectiveness of research”.

Tensions and Conflicts

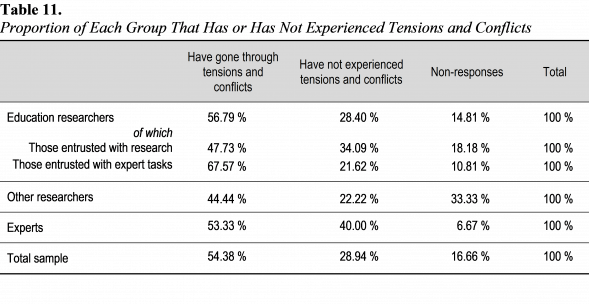

In the sample, most education researchers, and more generally most respondents, report having experienced tensions and conflicts in researcher-expert collaborations (Table 11).

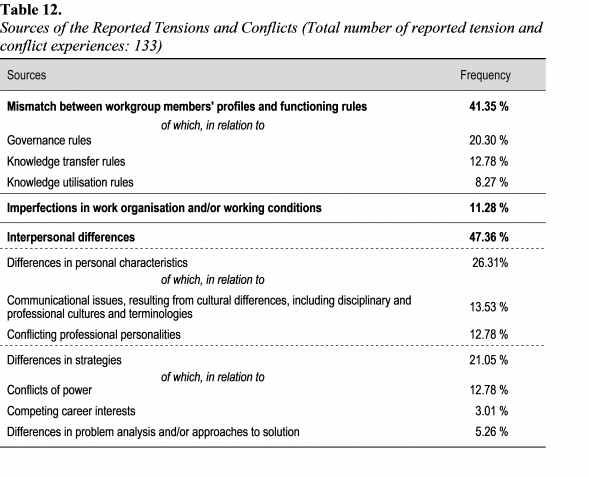

All possible sources of tension and conflict that were envisaged in the analytical framework could actually be found in the responses (Table 12). Conflicts are not so often related to work organisation or working conditions (only 11.28% of cases). Instead, they are mainly the result of interpersonal differences (47.36%) and mismatches between players’ profiles and functioning rules (41.35%). Among the interpersonal differences, those relating to culture and professional personalities are the primary sources of conflict (26.31%), although differences in strategies also play an important role (21.05%).

Experiences are very mixed in terms of the frequency of episodes of tension and conflict. Of the 48 respondents who addressed this item, 48% declared less than two episodes on average per year, 21% between three and six episodes on average per year, while 31% declared that tensions and conflicts were permanent.

Conflicts are generally of moderate intensity. Of the sixty respondents who rated the intensity of the tensions and conflicts they experienced, 81% rated the average intensity at 5 or less, on a scale of 1 to 10. Some episodes, however, may have been felt as violent and traumatic: 34% of these sixty respondents reported conflicts of extreme intensity, at levels 7 to 10.

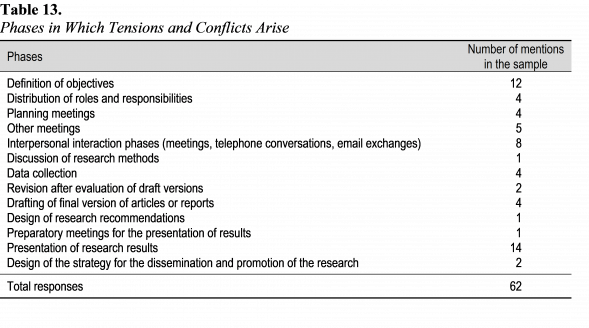

Some phases of the collaboration are particularly conducive to tension and conflict. Such is the case for the phases of defining objectives and presenting results, as well as for meetings and interpersonal contacts (Table 13).

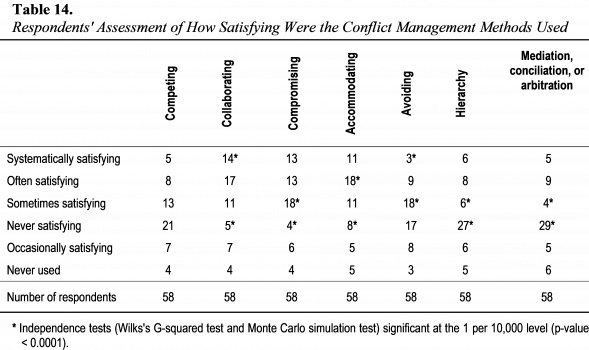

Apart from taking legal action and referring to standing institutional dispute resolution mechanisms, every other conflict management method that was listed in the analytical framework was actually used by the respondents. The frequency of use does not differ much from one method to another: between 52 and 55 uses for each method in the sample. However, not all methods were perceived as equally satisfying for resolving conflicts (Table 14). “Collaborating” is significantly more often cited than others as the approach that has consistently led to a satisfying resolution of conflicts. “Accommodating” is significantly most cited as often providing a satisfying resolution; “compromising” and “avoiding” are significantly more cited as sometimes leading to a satisfying resolution; institutional procedures (settlement by the hierarchy, mediation, conciliation, arbitration) are significantly more cited as failing to allow a satisfying resolution. “Competing” was used as often as the other approaches, however, no significant level of satisfaction could be identified from the responses.

Player Differences in Professional Personalities and Professional Cultures

Literature (Burkhardt, 2019; Stone et al., 2001) suggests that education researchers are being sidelined from education policy making because of their alleged disconnection from reality and preferences for dissenting views, speculative thinking, and small-scale research. This section aims to further explore how education researchers differ from education policy experts in terms of values and, beyond, in terms of professional personalities.

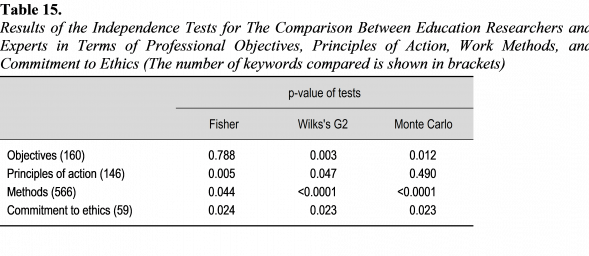

Five categories of objects are considered: not only values but also objectives, priorities, principles of action, and work methods. The survey respondents were requested to indicate the keywords that best express their position for each of these five categories. For each category, the keywords indicated by the education researchers (corpus 1) were compared to those stated by the experts (corpus 2). The closeness of both corpuses was then assessed using independence tests. The results suggest that the responses of the education researchers and those of the experts differ significantly in two ways. Firstly, education researchers and experts have significantly different objectives, principles of action, and work methods. Secondly, regarding values, education researchers and experts differ in terms of the declared attachment to respecting ethics (Table 15).

The null hypothesis of the tests is that there is no relationship between group membership (education researcher or expert) and the stated keywords. The null hypothesis is rejected if the p-value is less than 0.05. This is the case here in at least two out of the three tests, whatever the object category considered. It can therefore be concluded that in this sample, the stated keywords significantly depend on the group to which the respondent belongs.

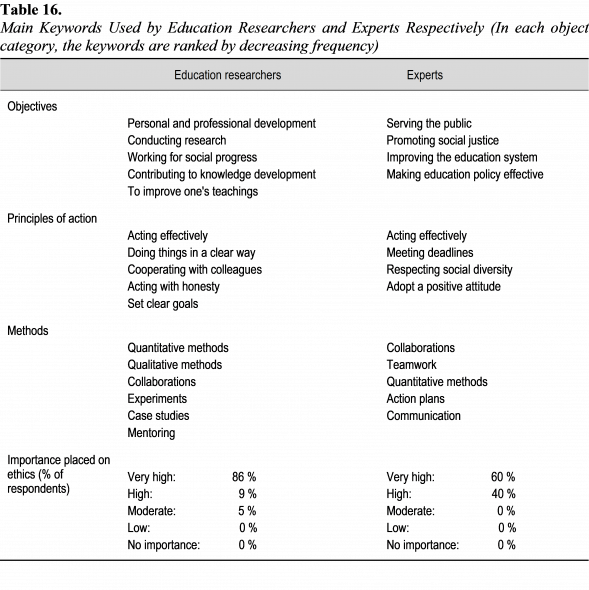

An examination of the most used keywords in each object category makes sense of the differences between the two groups (Table 16).

In terms of objectives, the sampled education researchers appear to be mostly oriented towards personal and professional development, research, and knowledge, while the experts appear to focus more on serving the public and improving the education system and policy. The principles guiding operational action reflect more administrative and social concerns among the experts, while the researchers stand out for their insistence on qualitative research methods. Finally, the structure of groups in terms of the declared intensity of attachment to ethical rules differs significantly.

These results confirm that the professional differences between education researchers and experts go beyond values and also affect objectives, principles of action, and work methods. However, no significant differences between the two groups could be found in priorities. Yet, such a difference in terms of priorities could be found between other researchers (from disciplines other than education) and experts, the former standing out for insisting on “innovation”, “research”, and “students”, in contrast to experts focused on “developing leadership in educational teams” and “teachers”.

In terms of values, the education researchers clearly stand out for their insistence on ethics. However, they did not significantly state in their free-text answers any other keyword that might have labelled their group, contrary to the other researchers, who significantly also expressed attachment to “truthfulness”. In particular, education researchers did not provide any significantly distinct keywords that could have been interpreted as expressing a preference for either singling oneself out, or speculative thinking, or individual/small team research.

Interpretation

The results obtained show that, on engaging in policy-making workgroups, the sampled education researchers have been faced with functioning rules at odds with their academic practices; disillusion over their input to policy making and the benefits from and conditions of participating in it; tensions and conflicts; and co-workers with different professional personalities and cultures.

It is therefore plausible to consider these points as possible factors of the lesser involvement of education researchers in the process of education policymaking. The idea is that a combination of self-exclusion and exclusion may be at play. Self-exclusion, on the one hand, as education researchers may tend to abstain from involving in policymaking, which may not appear to them as a privileged way for achieving their main objectives (personal and professional development, research, knowledge, teaching) and cultivating their methodological interests for quantitative and qualitative methods, experiments, and case studies. Those among them who nonetheless decide to go ahead report cases of research constraints other than of scientific nature; uncertain prospects for results translation into policy; and tensions and conflicts fuelled by differences in professional personalities and professional cultures as well as diverging work strategies and competing power and career interests.

On the other hand, exclusion also may take place as experts may have reservations towards a group that does not share the same professional personality and culture, at least in terms of objectives, principles of action, working methods, and approaches to ethics. This echoes previous comments by Stone et al. (2001).

Finally, this combination of self-exclusion and exclusion is likely to end up with (or at least contribute to) a lesser involvement of researchers.

Conclusion

The aim of this article was to analyse the reasons for the lesser involvement of education researchers in the making of public education policy. Education researchers’ involvement in education policy making is key to promoting research-informed education policy, and hence – still more important – research-based education practice. Existing literature points to factors such as policy players’ reservations towards pairing with education researchers, and the counter-productive impact of the latter’s preference for singling out one’s own views, speculative thinking, and individual or small team research. Based on a survey of education researchers and experts, this research confirms that exclusion may occur, but also highlights that education researchers may well exclude themselves due to the constraints, disillusion, conflicts, and the challenge of dealing with other professional personalities and cultures, which collaborating in policy-making workgroups entails.

However, the results presented here may not reflect the general situation of researcher-expert collaborations in the education policy-making process. Data collection was based on a small non-probability convenience self-selected sample. These results, therefore, do not pretend to reflect more than the characteristics of this sample, with the additional limitation that a survey is declarative in nature and data truthfulness, therefore, depends on respondents’ subjectivity.

That said, these results are of interest inasmuch as they highlight characteristics that were observed in (part of) the reality of collaborations between researchers and experts, even though it is not known whether their prevalence is high or low. In this sense, this article is exploratory, and further research is needed.

Further involving education researchers in the making of education policy would be in the best interest of both policy players and education stakeholders. Research may help reinforce the foundations, contents, and effectiveness of policies, and in particular, contribute to effective education. Mohajerzad et al. (2021) have shown that practitioners tend to have a high level of trust in research input, so it can be hypothesised that support from policy may reinforce this. Therefore, it might be worth further opening up the education policy-making doors for education researchers. On the education researchers’ side, keeping their distance from policy can certainly be to some extent, as can be seen from Luke (2003), a resistance reflex against risks of “neoliberal” moves. Yet, as can be understood from Gale (2006), participating in policy is also a matter of (re)gaining influence. Given the stakes, the education research communities might consider better valuing policy-making participation in their standards, cultures, conceptions, researchers’ professional identity and professional personalities, and in the handling of researchers’ curricula and careers. Reflecting on policy-making learning actions targeted to future researchers (Nagro et al., 2019) might be one example to start with.

References

Blake, R. R. & Mouton, J. S. (1964). The managerial grid. Gulf Publishing Company.

Burkhardt, H. (2019). Improving policy and practice. Educational Designer, 3(12).

https://www.educationaldesigner.org/ed/volume3/issue12/article46/pdf/ed_3_12_burkhardt.pdf

Estabrooks, C. A., Thompson, D. S., Lovely, J. J., & Hofmeyer, A. (2006). A guide to knowledge translation theory. The Journal of continuing education in the health professions, 26(1), 25–36. https://doi.org/10.1002/chp.48

Ferlie, E. & Geraghty, K. J. (2005). Professionals in public services organizations – Implications for public sector “reforming”. In E. Ferlie, L. E. Jr Lynn & C. Pollitt (Eds.) The Oxford handbook of public management (pp. 422–445). Oxford University Press.

Gale, T. (2006). Towards a theory and practice of policy engagement: Higher education research policy in the making. Australian Educational Researcher, 33(2), 1–14.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ766606.pdf

Goldman, B. M., Cropanzano, R., Stein, J., & Benson, L. (2008). The Role of Third Parties/Mediation in Managing Conflict in Organizations. In C. K. W. De Dreu & M. J. Gelfand (Eds.). The Psychology of conflict and conflict management in organizations (pp. 291–319). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Taylor & Francis Group.

Ion, G. & Iucu, R. (2015). Does research influence educational policy? The perspective of researchers and policy-makers in Romania. In A. Curaj, L. Matei, R. Pricopie, J. Salmi & P. Scott (Eds). The European Higher Education Area – Between Critical Reflections and Future Policies (pp. 865–880). Springer.

https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-20877-0.pdf

Ion, G., Marin, E. & Proteasa, C. (2019). How does the context of research influence the use of educational research in policy-making and practice? Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 18(2), 119–139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-018-9236-4

Luke, A. (2003). After the marketplace: Evidence, social science and educational research. Australian Educational Researcher, 30(2), 87–107. august aer 2003 (ed.gov)

Mohajerzad, H., Martin, A., Christ, J., & Widany, S. (2021). Bridging the Gap Between Science and Practice: Research Collaboration and the Perception of Research Findings. Frontiers in Psychology, 12:790451. Doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790451

Nagro, S. A., Shepherd, K. G., West, J. E., & Nagy, S. J. (2019). Activating policy and advocacy skills: A strategy for tomorrow’s special education leaders. Journal of Special Education, 53(2), 67–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022466918800705

Olson-Buchanan, J. B. & Boswell, W. R. (2008). Organizational dispute resolution systems. In C. K. W. De Dreu & M. J. Gelfand (Eds.). The Psychology of conflict and conflict management in organizations (pp. 321–352). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Taylor & Francis Group.

Smith, K., Fernie, S., & Pilcher, N. (2021). Aligning the times: Exploring the convergence of researchers, policy makers and research evidence in higher education policy making. Research in Education, 110(1), 38–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/0034523720920677

Stone, D., Maxwell, S., & Keating, M. (2001). Bridging research and policy. Radcliffe House, Warwick University.

Terzieva, M. & Morabito, V. (2016). Learning from experience: the project team is the key. Business Systems Research, 7(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1515/bsrj-2016-0001

Thomas, K. (1992). Conflict and conflict management: Reflections and update. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 13, 265–274. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.4030130307

Thomas, K. (1976). Conflict and conflict management. In M. D. Dunnette (Ed.). Handbook of industrial and organizational psychology (p. 889–935). Rand McNally.

Weiss, C. H. (1979). The many meanings of research utilization. Public Administration Review, 39(5), 426–431. https://doi.org/10.2307/3109916

Total views : 39996

Total views : 39996