What Is Meant By ‘Teacher Quality’ In Research And Policy: A Systematic, Quantitative Literature Review

Kane Bradford*, Donna Pendergast*, Peter Grootenboer**

*School of Education and Professional Studies, Griffith University, Australia

**Griffith Institute for Educational Research, Griffith University, Australia

Education Thinking, ISSN 2778-777X – Volume 1, Issue 1 – 2021, pp. 57–76. Date of publication: 24 November 2021.

Cite: Bradford, K., Pendergast, D., & Grootenboer, P. (2021). What Is Meant By ‘Teacher Quality’ In Research And Policy: A Systematic, Quantitative Literature Review. Education Thinking, 1(1), 57–76. https://analytrics.org/article/what-is-meant-by-teacher-quality-in-research-and-policy-a-systematic-quantitative-literature-review/

Declaration of interests: The authors have no interests to declare.

Authors’ notes: Kane Bradford is a PhD candidate. His research is examining the impact of public policy on the work and lives of teachers. In addition to his research, Kane is a practicing secondary school teacher and executive leader and has worked in public policy in Australia. Professor Donna Pendergast is Dean and Head, School of Education and Professional Studies at Griffith University. Donna has an international profile in the field of teacher education, particularly in the Junior Secondary years of schooling, which focuses on the unique challenges of teaching and learning in the early adolescent years. Professor Peter Grootenboer is currently the Director of the Griffith Institute for Educational Research at Griffith University. His research focus is on four key inter-related areas: practice and practice theory, action research, middle leadership (middle leading) and mathematics education. His research interests within these fields include: professional practice and practice development; leading change; and the affective dimension of learning.

Copyright notice: the authors of this article retain all their rights as protected by copyright laws. However, sharing this article – although not in adapted form – is permitted under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives BY-ND 4.0 International license, provided that the article’s reference (including author name(s) and Education Thinking) is cited.

Journal’s area(s) of research addressed by the article: 19. Educational Policy; 63. Teacher Education and Development; 50. Quality Education.

Abstract

The notion of ‘teacher quality’ is a concept that has dominated education research and policy for decades. While the terminology is widely accepted and used in the literature, it lacks a clear and consistent understanding and application in the field. Furthermore, the underpinning factors relating to ‘teacher’ and ‘teaching’ quality are regularly used interchangeably and often unintentionally. As a result, while the concept of ‘teacher quality’ is widely used and forms the basis of critical policy reform in Australia and internationally, its foundations are compromised due to this lack of clear definition and common intent. Moreover, with such disparate understandings and applications of ‘teacher quality’, assessing the viability and impact of policy and performance and comparing systemic outcomes in this area, in schooling systems, is increasingly difficult. Within this context, this study seeks to draw out, from a critical analysis of the literature, what is meant when the term ‘teacher quality’ is used in research and policy. A deliberate emphasis was placed on the Australian context with the intention of situating the findings in this setting. To achieve this, a Systematic, Quantitative Literature Review (hereafter SQLR) was conducted, adopting the formal methodology of Pickering and Byrne (2013). The SQLR produced 215 articles after exclusion protocols were applied. Forty-four themes emanating from these papers revealed that ‘teacher quality’ as a concept is invariably interconnected with notions of ‘teaching quality’, but the underlying constructs lack consistency and definition, despite an assumption that there is a shared understanding of the meaning. The findings suggest that the lack of clarity around this construct has allowed policy to drive a prevailing narrative, most recently characterised by a measurement and accountability agenda. As a result, professional expertise as well as interpersonal and psychosocial factors shown to impact the quality of teachers and their practice have been marginalised. It appears that what actually matters, in terms of impact in schools and performance of educators, is in the union of these concepts; ‘who’ teachers are and ‘what’ they do.

Keywords

Teachers, Teaching, Quality, Policy, Education Policy, Australia

In the past 20 years, public discourse relating to school education has been dominated by a focus on the quality of teachers (Berkovich & Benoliel, 2018; Churchward & Willis, 2019; Fraser, 2017; Hartong & Nikolai, 2017; Mockler, 2018; Nordin & Wahlström, 2019; Scholes et al., 2017; Simmie et al., 2019; Skourdoumbis, 2019). The term ‘teacher quality’ has emerged as a prevailing concept that permeates media and policy portrayals as a key factor impacting the core business of schools and student learning outcomes (Barnes & Cross, 2018; Nordin & Wahlström, 2019).

The work of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) and its Program for International Student Assessment (PISA) has set the trend internationally by ranking the performance of respective nations school students’ scores on standardised tests. As nations have sought to improve their position on the league tables that are used to report their performance, education policy has increasingly focussed on demonstrating quality – particularly teacher quality. In the Australian setting, this focus on the quality of teaching “manifests in the development of standardised national professional standards for teachers, a national focus on teacher performance, and school improvement templates that foreground teacher expertise” (Scholes et al., 2017).

Where student achievement is in focus, teacher quality is regularly characterised as both the problem and the solution in the media (Baroutsis, 2016; Mockler, 2018) and there appears to be a disproportionate connection drawn between teacher performance and student achievement. Skourdoumbis (2017a), for example, highlights the extent to which policy has come to draw direct, ‘linear’ inferences between cause and effect when it comes to teachers and student outcomes.

The idea that ‘better’ teachers lead directly to better test scores in PISA has resulted in a range of policy actions aimed at lifting the performance of teachers, thus throwing the concept of ‘teacher quality’ into the limelight (Berkovich & Benoliel, 2018; Churchward & Willis, 2019; Martínez et al., 2016). The relentless fascination with this agenda, portrayed mostly through the media, detracts from the attractiveness of teaching and challenges notions of professionalism (Mockler, 2018).

Establishing a Definition

Despite its common and wide use in the literature and in the field, there is no consistent definition or understanding of the term ‘teacher quality’ (Barnes & Cross, 2018; Scholes et al., 2017). The definition of teacher quality is rarely stated – it is assumed that there is a shared understanding. However, as already noted, the concept is often muddled and used interchangeably with ‘teaching quality’, a concept more aligned to the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of practice rather than the ‘who’. Recent trends also point to a disconnect between the defining characteristics of teacher and teaching quality, and associated policy solutions enacted globally (Fraser, 2017; Fullan et al., 2015; Nordin & Wahlström, 2019; Skourdoumbis, 2017b; Tsai & Ku, 2020).

The literature reveals there is tension in application and definition of ‘teacher quality’, and there seems to be an incongruence in the various understandings of ‘quality’ that are present. Fransson et al. (2018) describe it as a ‘mega-narrative’, and while it appears widely in the literature and is used variably in research, the concept is rarely applied with consistent interpretation (Tsai & Ku, 2020). Further, there is a disconnect between two commonly held interpretations of the phraseology – is this considering the quality of ‘teachers’ or ‘teaching’ practice? (Churchward & Willis, 2019; Gitomer, 2019)

The research points to a recent trend in applying the concept to notions of professional practice and accountability. That is to say, ‘teacher quality’ regularly appears against frameworks, standards and rubrics which seek to unpack the skills and capabilities of practitioners to provide a road map to expertise and performance (Fransson et al., 2018). This is held to be a largely reductionist interpretation of ‘teacher quality’, encouraging a discourse which sees the complex nature to teaching and learning reduced to lists of behaviours, many of which don’t allow for variance of context, cultures, learners, environment or practitioner (Fransson et al., 2018; Gitomer, 2019; Reid, 2019; Sinnema et al., 2017; Spillman, 2017). This is a concern as it would appear that there is no single or complete measure for quality. Gitomer (2019) further claims that in reality, the pursuit of this is foolish, it’s a better understanding of the interrelated factors and subtle nuances of teaching quality that should have our attention. With a push for greater professional accountability for teachers and in the absence of clarity around the concept of ‘teacher quality’, there is a tendency to measure that which is readily accessible, not always the most insightful or useful to teachers themselves (Mockler & Stacey, 2021, p. 185).

Exploring Teacher Quality

La Velle and Flores (2018) sought to unpack the nature of a teacher’s work, reviewing the research pertaining to the knowledge and practices associated with teaching. They found that the role of a teacher and the knowledge required for practice spanned a broader range of skills than most training courses can handle. They do need to master the technical dimension of teaching, but their profession involves more than that. Issues such as reflection, emotions, beliefs, dispositions, agency, professional values, etc. are key in developing as a teacher along with robust knowledge (La Velle & Flores, 2018, p. 524).

In reference to the elements which underpin teacher quality, Nordin and Wahlström (2019) found that curriculum and pedagogy are prominent. These aspects highlight the challenges with establishing an agreed definition for quality, where one is invariably concerned with what is taught and the other how it is taught. Gore (2021) refers to the challenges of this ‘slippage’ where the solutions in research and policy often seek to ‘fix’ teachers, when the effort may be better aligned to looking at their practice or a combination of person and practice. Stolz (2018) provides a genealogical analysis of the concept of ‘good’ as it is applied to teaching, noting repeated characterisation of ‘good’ as a construct relating to either applied science or practice and a vocational calling. The idea that teaching comprises two distinct subsets is supported regularly through the research, with many noting that the publicly held notion of ‘quality’ often manifests in this sort of separation.

While the focus is on the type of teacher, their quality and effectiveness, more pressing issues from within education that work towards actively engaging with the complexities of the twenty-first century are given insufficient attention (Skourdoumbis, 2017b, p. 56). Scholes et al. (2017) offer a different perspective in addressing the apparent separation between ‘teacher’ and ‘teaching quality’. Specifically, they note that ‘decoupling’ these terms is largely counterintuitive, given both have a direct effect on students and their learning. Therefore, their contention is that the construct ought to be a clear marriage of the underlying elements of both the individual and their practice.

The informing literature points to a separation between the markers of teacher and teaching quality, potential policy solutions and the policy enacted globally. The evidence suggests that while there are numerous factors which underpin ‘quality’ regarding teachers and/or teaching, policy solutions, espousing to be concerned with ‘teacher quality’, are almost exclusively found in measurement, evaluation, and accountability domains. In part, this focus has been attributed to the growing influence of agencies such as the OECD and high stakes testing which ranks countries by student test performance (Araujo et al., 2017).

By exploring the context for this study, it is evident that reaching a shared understanding of teacher quality as it impacts the student experience is important work. Hence, this paper reports a study exploring the concept of ‘teacher quality’ as it is applied to the context of education research and policy. The study explores the term in the literature and in policy statements in Australia and internationally, and then addresses the absence of a clear and consistent definition of the term, noting the challenges this presents given the significance of the notion in the work and lives of teachers. Finally, a case is made for the need to rethink interpretation and application of ‘teacher quality’ discourses in research and policy agendas.

Method

This study employed a SQLR using the approach outlined in Pickering and Byrne (2013). The method applies a systematised approach to the search, requiring an unbiased assessment of content against clearly established criteria relevant to the field. This means that while the subject of teachers, their practice and definitions or interpretations of quality are discussed widely in the literature, only those contributions that meet the timing and inclusion parameters of the SQLR can be included for analysis. In this instance, the SQLR sought to capture research in relation to teacher quality, particularly as it pertains to policy and the Australian context.

The disciplined approach of a SQLR means that researchers cannot discriminate in the selection of literature but must instead provide a comprehensive account of the literature that meets the inclusion criteria. SQLR papers are growing in prominence across a number of fields, including education, with the benefits of a robust and comprehensive review method attracting researchers to the approach. For example, Ronksley-Pavia et al. (2019) explored empirical studies with an interest in multi-age education in small school settings, with a specific focus on curriculum and pedagogy. The SQLR method outlined by Pickering and Byrne (2013) utilised in these studies, is characterised by its rigour, comprehensiveness and reproducibility. A review conducted with this method involves establishing clear inclusion/exclusion parameters before searches are conducted. This ensures objective data capture and therefore, means that any findings would be replicable by another researcher conducting the same SQLR.

The method is best applied in concert with a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis – PRISMA statement (Moher et al., 2009) which summarises the search categorisation as the literature is captured and filtered for inclusion. The SQLR (Pickering & Byrne, 2013) involves the following steps:

As this study is concerned with research, public policy and teacher quality, the review only considered journals published in the past five years. A comprehensive search of the following online databases formed the basis of the review: Griffith University Library Catalogue, A+ Education (via Informit), Education Database, Emerald Fulltext, ERIC (via ProQuest), Sage Journals Online, SpringerLink and Taylor and Francis Journals. Papers which appeared in the search dealing with the terms ‘teachers AND teaching’ in combination with ‘quality’, ‘good’, ‘excellent’, OR ‘performance’ AND ‘policy’ OR ‘education policy’ were included. Duplicates were recorded but factored only once in the final count. Studies were screened to ensure alignment to the focus of this review. The results are provided at Figure 1.

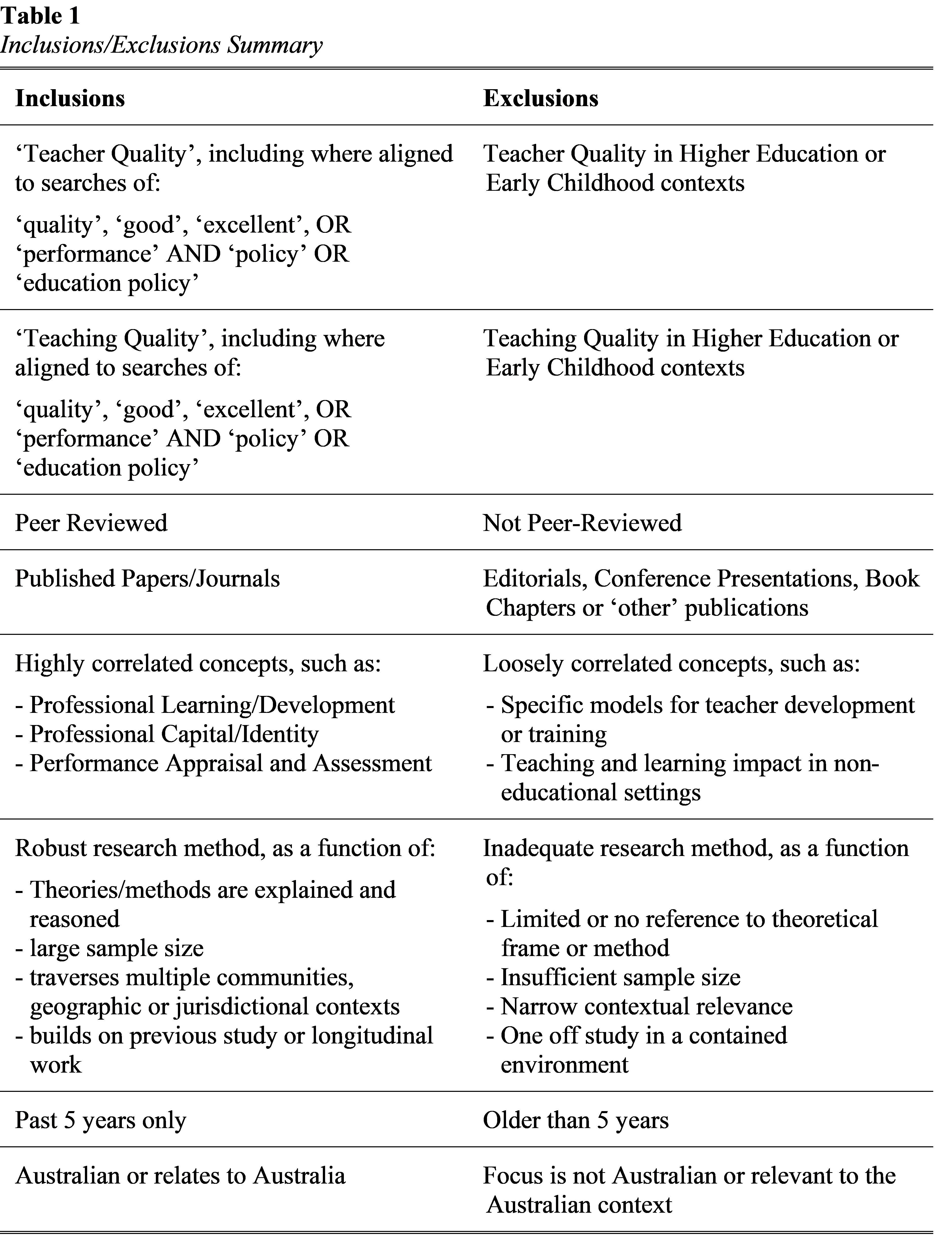

Table 1 provides a list of inclusion and exclusion categories. Papers with a focus on teacher or teaching quality in the Higher Education or Early Childhood contexts were not considered in this review. Only peer reviewed journals were considered for this search, and editorials, book chapters or other publications were discounted. Given the broad nature of the research field, initial scanning captured more than 18,000 records. Before full text analysis, the number was refined down further against the above criteria, but also articles with highly specialised sub-set focus in the area of study were discounted (for example – ‘professional learning’ in general terms as relating to teacher quality was considered, but ‘building quality online modules for teachers’ would be discounted due to its narrow focus). Further, research which exhibited significant limitations, particularly by sample size or focus of the study was off topic or provided little to no evidence to support claims (editorialised), were discounted. Australia was retained as a focus in searching, which netted results that came from Australia but also allowed for international studies which held relevance to the national context to be included or comparative analysis to be considered.

Results

The review was concerned with depictions of quality as related to teachers and teaching providing clarification or definition to the concept of ‘teacher quality’, but also as it is applied in education policy. In this regard, the systematic approach required a detailed cataloguing of the key topics and themes that emerged throughout the literature.

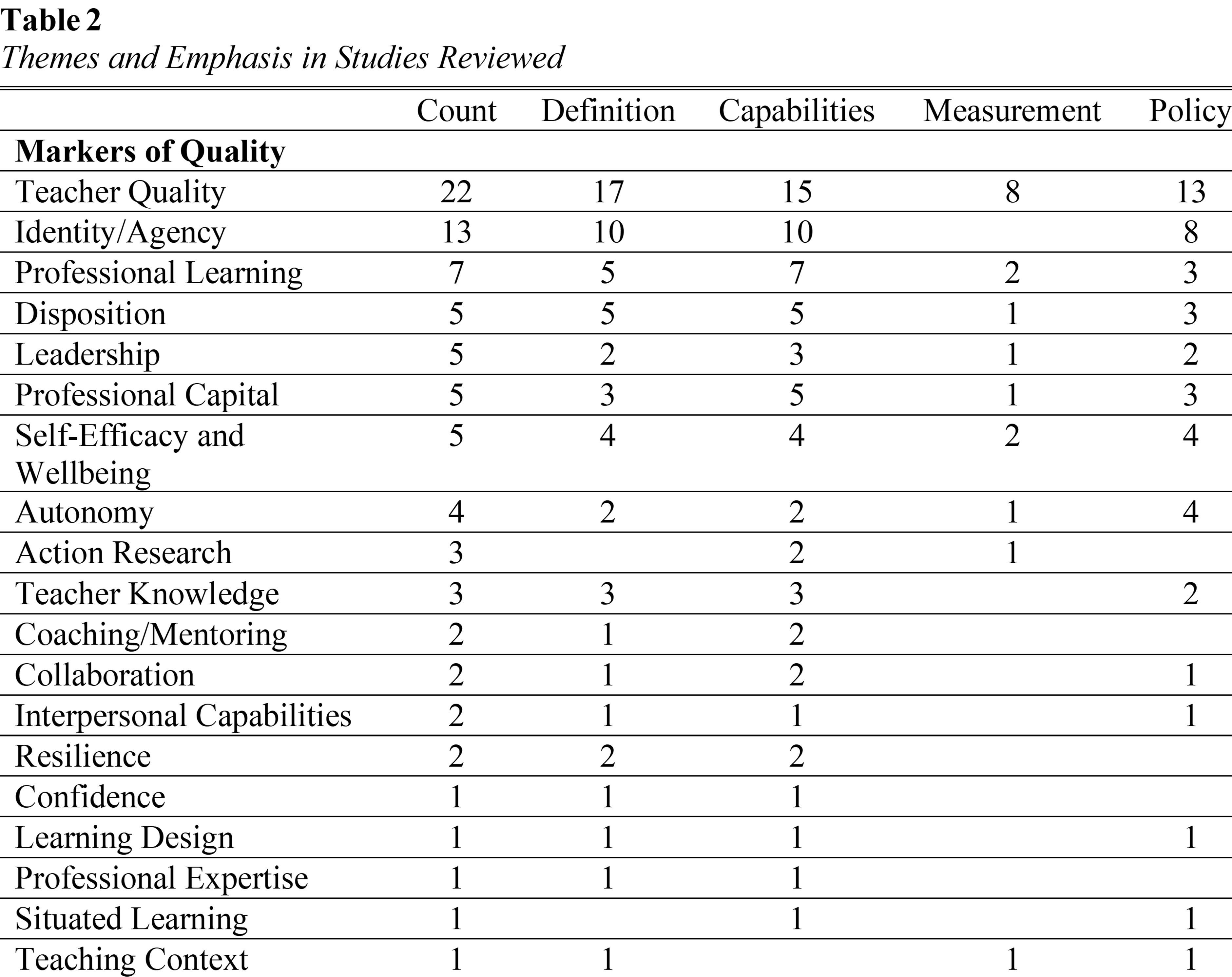

Table 2 presents the 44 themes that emerged from the SQLR. These 44 themes have been further categorised into two broader organisers: (i) those studies dealing with the ‘markers of quality’ and (ii) those dealing with how policy has come to define quality.

The context for the 44 themes was also noted as a function of five factors: the frequency count; definition; capabilities; measurement; and policy. An explanation of these five factors is presented in Table 3.

The findings reveal the broad range of concepts associated with ‘teacher quality’. There was a trend toward attempts to clarify and define the concept in much of the literature considered, with most items linking directly to capabilities or definition. The large number of themes (44) reflects the complexity of the concept. What follows is an analysis of the frequency and emphasis of these factors.

In addition to observing these themes as a function of research and policy literature classifications, three broader thematic trends were observed. The SQLR revealed that all publications that met the inclusion criteria, and the 44 themes identified, dealt with the concept of ‘teacher quality’ in one of or a combination of the following ways:

Each of these broader thematic trends will now be considered in turn.

Teacher and Teaching Quality

When exploring notions of ‘teacher quality’, the literature is quite disparate in dealing with the human factors which underpin performance and the pedagogical traits linked to student outcomes. Of the themes identified by the SQLR, the ‘quality’ discourse appeared in the findings mostly through the research and policy attempting to define the term and usually between analysis of teachers and their practice.

More specifically, there is an unresolved tension not only in the definitions, but in the research as to which has the greatest impact on students and their learning: who the teachers are or what they do. This furthers adds to the confusion in determining what policy ought to be concerned with in relation to ‘quality’. Across the studies considered, this separation factors prominently; however, they are often unintentionally used interchangeably. Whether they even ought to be considered independently or as a unified construct remains unresolved.

As the focus of this study was on teachers, associated concepts typically aligned to ‘teaching quality’ usually surfaced in the context of the practitioner’s capability to deploy curriculum and pedagogy for impact. The research suggests that where there is an attempt to link performance to outcomes, particularly where the outcomes relate to students as the core business of schooling, it is difficult and potentially unnecessary to separate the traits (Scholes et al., 2017) . As Reid (2019) states,

Curriculum and assessment can be controlled—but the pedagogy and practice that is essential if curriculum goals are to be realised must be enacted, in situated, and always changing, contexts: produced in the relationship of teacher and students. (Reid, 2019, p. 724)

Mostly, the findings indicate that where a teacher is performing, their curriculum and pedagogical choices will be sound and where there are sound curriculum and pedagogical choices, there will be a performing teacher. However, quality is not limited to the practice of the teacher.

Measurement, Accountability and Professional Agency

The literature meeting the inclusion criteria for this SQLR regularly questioned the emphasis of the connection between teacher quality and student test results. The findings of the SQLR showed that research and policy which addressed measurement and accountability was often linked with attempts to establish deeper understandings of teacher quality. There was a concurrent theme that also suggested that the presence of this link may be largely a result of policy makers and government preferencing that which is more easily measured. This raises the question of:

…whether we are measuring what we value about education, that is whether we seek to establish whether education is indeed doing what we hope and expect from it or whether we have created or are creating a situation in which we have come to value what is being measured” (Biesta, 2015, p. 351).

This also sets up a challenging outlook for the education sector, where the emphasis is on improving outcomes from students, and teachers are mostly held accountable for how well those students perform on high stakes international tests (Biesta, 2015; Cloonan et al., 2019). Schleicher (2016), as a representative of the OECD, reflected this challenge in reference to PISA: “… educational success is no longer mainly about reproducing content knowledge, but about extrapolating from what we know and applying that knowledge in novel situations” (Schleicher, 2016, p. 2).

Research which has considered the development and application of performance standards and frameworks internationally shows there are challenges with consistently measuring and evaluating teaching practice in reliable and comparable ways. Fransson et al. (2018) note that the Australian Professional Standards for Teachers – APST (Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership, 2011) support one particular interpretation of teaching as an evidence-based undertaking where success is defined by observable and measurable outcomes. This evidence-based/evidence-informed framing of practice is found regularly in the literature. Teachers are positioned as expert users of data, who deploy sophisticated measurement techniques and apply findings in highly customised ways to maximise outcomes for their students (Brown & Greany, 2018). The extent to which this occurs, and that teachers are equipped to operate in this way or that it has a meaningful, lasting impact on students is debated throughout the literature, despite its disproportionately high prevalence as a discourse in policy; particularly where it is connected to high performance and teacher quality (Wachen et al., 2018).

The personal capabilities and attributes that are evident in quality teachers is also broadly characterised in the literature. The socio-emotional traits of the high performing teacher consistently surfaced along with concepts of emotional intelligence, adaptability and flexibility, professional judgement and expertise and self-efficacy (Buttner et al., 2016; Durksen & Klassen, 2018; McNally & Slutsky, 2018).

It is notable that while this study highlights a range of factors which impact quality of teachers and teaching, particularly in relation to professional agency elements such as emotional intelligence, adaptability and flexibility, professional judgement, expertise and self-efficacy, policy is dominated by a measurement and accountability agenda.

Policy as Defining Quality

Regarding the policy literature examined in the SQLR, the findings showed that policy regularly sought to respond to but also drive the very definition of ‘teacher quality’. Where ‘quality’ constructs are considered in respect to public policy debate and directions, there is a tendency to preference the elements of the concept that are more easily identifiable and measurable. This manifests regularly in respect to ‘teaching quality’ where the pedagogical decisions of educators can be more readily observed and critiqued. Moreover, the ‘what’ and ‘how’ of teaching forms the centre point of much of the international agenda with respect to policy. The more complex aspects of teaching and learning, typically the human factors, are either deprioritised or marginalised in considerations of ‘teacher quality’. What remains is a distinct trend in international policy whereby the focus is on what can be readily seen and measured (Sinnema et al., 2017; Skourdoumbis, 2017b; Stolz, 2018; Tsai & Ku, 2020). There are obvious implications for further research in this area, specifically in better understanding what can be done with the myriad of factors the research tells us make a difference to ‘quality’ that have yet to be taken up in education policy agendas.

The SQLR shows an emphasis, through education policy, on teachers and their practice. The concepts of improving, enhancing, supporting or driving performance of teachers in schools is a common policy focus for many countries across the globe (Akkari & Lauwerier, 2015; Biesta, 2015; Lingard & Lewis, 2017; Lubienski, 2018; Nordin & Wahlström, 2019; Skourdoumbis, 2017b; Steiner-Khamsi, 2016). International agencies such as the OECD are instrumental in both garnering support for and providing guidance toward responses in relation to teacher and teaching quality. Moreover, the OECD and associated processes such as PISA, Progress in International Reading Literacy Study (PIRLS) and/or Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) assessments are identified as holding prominence in the direction of education policy across the globe (Akkari & Lauwerier, 2015; Biesta, 2015; Fraser, 2017; Lingard & Lewis, 2017; Murgatroyd & Sahlberg, 2016).

Berkovich and Benoliel (2018) found that the OECD use discourses of fear to frame teachers as the problem, to promote reliance on systems and organisations and to encourage greater regulation and accountability in the name of improvement. Certainly, this is a view that is supported in the literature, which often questions the reliability of OECD data and reporting, its influence in driving the global policy agenda and the degree to which nations have come to rely on its work as the basis for policy making (Berkovich & Benoliel, 2018)

Whether globally or locally driven, there’s a tendency for education policy platforms to be driven by student outcomes, and more specifically, student results on comparable assessment instruments (Barnes & Cross, 2018). Skourdoumbis’s (2017a) work highlights the ‘misappropriation’ that ties teacher quality and performance so directly to student outcomes of this kind. The evidence suggests that while teachers and their performance have an impact on student outcomes, school performance, particularly student results on standardised tests, is impacted by a myriad of factors, many of which are outside of the direct influence of the classroom practitioner (Lee, 2018; Skourdoumbis, 2017a, p. 205)

Discussion

This SQLR set out to apply a ground-up approach to understand what is meant when the term ‘teacher quality’ is used in research and policy. Through this analysis of the literature the study reveals that while ‘teacher quality’ and ‘teaching quality’ are related, there are distinct differences in the underlying elements which apply to a definition of each. The interconnection between these concepts to the life and work of teachers is apparent in the literature, whether through public perception, media or in government policy that seeks to direct. While this study sought to establish a clear and consistent definition of ‘teacher quality’, it is apparent that the answer lies in a combination of factors that broadens the field to not only issues relating to ‘who’, but also the ‘what’ and ‘how’. That is, if student outcomes not only on test scores but on a range of measures is the goal, then research and policy ought to be concerned with who is teaching, what they are teaching and how they are teaching. In this regard, a union of constructs between ‘teacher’ and ‘teaching’ quality appears the more appropriate path. Of the 44 themes elicited from the SQLR, a number are notable as a function of frequency or as areas for further exploration, important in the context of defining quality and advancing policy.

The Nature of Professional Expertise

There are multiple understandings/perspectives of ‘quality teaching’ in the studies considered, many emphasising specialist content or pedagogical expertise as central to the quality conversation. These range from those which discuss an evident pedagogical hierarchy in teaching (e.g. senior teachers are better/know more) and highlight low ethical trust in teachers (particularly from parents and between teaching colleagues) (Simmie et al., 2019).

Simmie et al. (2019) found that our understandings of quality are becoming a ‘scientificity’, where “[t]he concept of ‘good teaching’ is reconfigured within a new ‘scientificity’ as a clinical practice of standardised knowledge, and prescriptive knower dispositions, based on a self-steering entrepreneurial audit culture ” (Simmie et al., 2019, p. 55). This sees content knowledge privileged in teaching practice, the human aspects of the role largely marginalised (Fransson et al., 2018).

The relationship between strength of content knowledge and instructional performance appears to be strong. Studies have found that students report enhanced quality when their teacher displays strong content and general pedagogical knowledge and teachers themselves report increased confidence in their capabilities where they have particular grasp of content areas to be delivered (König & Pflanzl, 2016).

Costello and Costello (2016) make particular note of the impact prescribed curriculum has on a teacher’s sense of self-efficacy and professional identity. In instances of tightly mandated curriculum, they found that the expert status of the practitioner is compromised and the mindset of the teacher shifts from that of a professional to one of accountability (Costello & Costello, 2016, p. 852).

The research suggests that quality practitioners exhibit inherent professional qualities that sit largely outside of prescribed standards and frameworks (Sinnema et al., 2017; Stolz, 2018). Moreover, the evidence suggests that quality is present where the teacher is able to apply professional judgement and adapt action and practice to suit the needs of learner and context.

Significance of relationships, interpersonal and psychosocial factors

Building effective learning relationships with students is considered central to quality teaching and learning. The teacher’s ability to forge meaningful relationships and to move beyond prescribed standards and frameworks to connect with their students is held to be of critical importance to performance (McNally & Slutsky, 2018; Stolz, 2018). Buttner et al. (2016) suggest that traits such as agreeableness, conscientiousness and openness to experience had a direct impact on teacher quality, particularly when working with difficult students.

Notions of professional capital as the foundation to teacher status, professionalism and thus performance is evident across the shared work of Fullan et al. (2015). In a global policy environment that is typified by calls for greater accountability, the authors make a consistent argument for accountability as an internal rather than external construct. Where this occurs, teachers develop self-efficacy and work with a greater sense of professionalism leading to targeted and more reflective practice which can have considerable impact on student and school performance. This model calls for the development of the professional capacity of the teaching profession and for renewed emphasis on the profession’s shared responsibility for continuous improvement in the pursuit of student outcomes (Zeichner & Hollar, 2016).

Prevalence of Measurement, Accountability and Testing Systems

The literature heavily references the more recent proliferation of teacher performance assessment tools and resources (Gitomer, 2019; Paugh et al., 2018; Steinberg & Kraft, 2017). As the policy push continues toward measurement and accountability, the invariable next step is the development of reliable instruments through which to understand impact. As has been addressed previously, there is an overstated and often misrepresented causality between teacher performance and student outcomes (Gitomer, 2019; Skourdoumbis, 2017a). Moreover, it is important to consider the range of variables that will affect outcomes in like classrooms. A measurement, using the same method or instrument, may net different results in different classrooms but not always because of the quality of the classroom teacher (Gitomer, 2019, p. 69).

The research literature also highlights that in many instances, that testing instruments can be less significant as a vehicle for change when set against the context through which the results are applied. Steinberg and Kraft (2017) revisited the research of the ‘Measures for Effective Teaching’ (Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, 2013) data to show how different the interpretations and outcomes can be when weightings are adjusted to cater further for context or emphasis. Moreover, the data will provide a very different reading depending on where the emphasis is placed by the policy maker (Martínez et al., 2016).

In the Australian policy context, the Commonwealth Government’s ‘Action Now: Classroom Ready Teachers’ (Australian Government, 2015) platform established a ‘reform’ narrative in relation to the Australian system and its teachers; specifically identifying teachers and teacher education as ‘problems’ in need of resolution (Churchward & Willis, 2019; Rowe & Skourdoumbis, 2019) . As Rowe and Skourdoumbis (2019) suggest, despite attempts to depict the changes as progressive and growth oriented “…the reforms are ideologically, politically and epistemologically rooted within a framework of teacher deficiency” (Rowe & Skourdoumbis, 2019, p. 55). Further, the reforms reinforce a view of teacher quality, in a policy sense, that is based almost entirely on student outcomes as a function of international test scores (Barnes & Cross, 2018). In real terms, the reforms have brought greater accountability and standardisation to registration and accreditation requirements and initial teacher education offerings in Australia.

Teacher education in Australia is characterised, particularly in recent policy, as failing. Several studies suggest that this conclusion is baseless and elicits a call to action that may not be necessary.

…while many agree that teacher quality must be maintained, there are well founded fears around the popularizing of a myth that University Education courses are letting just anyone into their programs, or are graduating sub-standard teachers. (Scholes et al., 2017, p. 29)

In pursuit of greater accountability and with a view to better articulating the work and performative stages of educators, professional standards have formed the basis of much of the international policy agenda in Education. Professional standards exist in some form or another in many countries, with some used as guidance, some used as a compliance mechanism to monitor and manage the standard of those in classrooms and admitted to practice, and others used in idea only.

Professional standards are also characterised as guiding or defining the markers of quality practice, both from the policymaker’s and teacher’s perspective. However, it has been noted regularly in the literature that this attempt to catalogue the aspects of performance evident in teacher practice is incredibly limiting. By design, standards will always struggle for relevance across all teaching and learning contexts and will subconsciously preference particular views of ‘quality’, as addressed previously (Scholes et al., 2017). In the Australian cases cited through this study, the authors found that teachers mostly use the APST to meet their accreditation requirements, in presentations and research and almost never to inform or refine practice (Bourke et al., 2018, p. 91).

Conclusion

This SQLR reveals there is not a consistent definition or understanding of what is meant when the term ‘teacher quality’ is used in the literature, and while there is tacit acceptance of the concept, particularly as it is applied to policy, it is functionally interchanged throughout subsequent studies with varying degrees of fidelity.

This creates a problem, which is exacerbated when the concept is tested in the broader context, manifesting in public and policy discourses. The use of ‘teacher quality’ as a concept found across the literature and particularly as applied in policy, often lacks ‘precision’, “…offering limited purchase on what quality actually entails…” (Scholes et al., 2017, p. 19).

Further, despite these tensions, there is a predominance, evidenced in policy, to focus on those aspects of teaching that are most readily observable and measured. Interpretations of the concept reside mostly in that which is easily explained and rationalised, resulting in a compromised application. If measurement and analysis of teaching and learning interactions is reduced to a scientific problem, the more complex facets of the profession will continue to be marginalised in discussions about quality (Skourdoumbis, 2017b, p. 44). This presents an opportunity for further research into interpretations of quality and how these are applied to inform policy decisions.

This study generated 44 themes from the literature with regards to teacher and teaching quality, with guidance as to the underlying concepts which positively affect performance on each facet. From the literature reviewed, it appears that policy makers preference measurement and accountability-based solutions with a limited focus on the human and professional factors associated with teachers and their practice. Surprisingly, policy solutions which build professional identity through fostering self-efficacy and agency and empowering the individual are limited. Equally, policy which identifies and supports the interpersonal capabilities shown to impact teaching and learning are largely absent. There is an opportunity to refine the standards of quality we apply to teachers and their practice and to establish an understanding of what is meant when the term ‘teacher quality’ is used in the literature.

References

Akkari, A., & Lauwerier, T. (2015). The Education Policies of International Organizations: Specific Differences and Convergences. Prospects: Quarterly Review of Comparative Education, 45(1), 141-157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11125-014-9332-z

Araujo, L., Saltelli, A., & Schnepf Sylke, V. (2017). Do PISA data justify PISA-based education policy? International Journal of Comparative Education and Development, 19(1), 20-34. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCED-12-2016-0023

Australian Government. (2015). Action Now, Classroom Ready Teachers Report. Retrieved from https://www.dese.gov.au/teaching-and-school-leadership/resources/action-now-classroom-ready-teachers-report-0

Australian Institute for Teaching and School Leadership. (2011). Australian Professional Standards for Teachers. Retrieved from https://www.aitsl.edu.au/teach/standards

Barnes, M., & Cross, R. (2018). ‘Quality’ at a cost: the politics of teacher education policy in Australia. Critical Studies in Education, 1-16.

https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2018.1558410

Baroutsis, A. (2016). Media Accounts of School Performance: Reinforcing Dominant Practices of Accountability. Journal of Education Policy, 31(5), 567-582.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2016.1145253

Berkovich, I., & Benoliel, P. (2018). Marketing teacher quality: critical discourse analysis of OECD documents on effective teaching and TALIS. Critical Studies in Education, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2018.1521338

Biesta, G. (2015). Resisting the Seduction of the Global Education Measurement Industry: Notes on the Social Psychology of PISA. Ethics and Education, 10(3), 348-360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2015.1106030

Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation. (2013). Measures for Effective Teaching. Retrieved from http://www.metproject.org/reports.html

Bourke, T., Ryan, M., & Ould, P. (2018). How do teacher educators use professional standards in their practice? Teaching and Teacher Education, 75, 83-92.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.06.005

Brown, C., & Greany, T. (2018). The Evidence-Informed School System in England: Where Should School Leaders Be Focusing Their Efforts? Leadership and Policy in Schools, 17(1), 115-137. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2016.1270330

Buttner, S., Pijl, S. J., Bijstra, J., & Van den Bosch, E. (2016). Personality traits of expert teachers of students with EBD: clarifying a teacher’s X-factor. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 20(6), 569-587.

https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2015.1100222

Churchward, P., & Willis, J. (2019). The pursuit of teacher quality: identifying some of the multiple discourses of quality that impact the work of teacher educators. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 47(3), 251-264.

https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2018.1555792

Cloonan, A., Hutchison, K., & Paatsch, L. (2019). Promoting teachers’ agency and creative teaching through research. English Teaching: Practice & Critique, 18(2), 218-232. https://doi.org/10.1108/ETPC-11-2018-0107

Costello, M., & Costello, D. (2016). The Struggle for Teacher Professionalism in a Mandated Literacy Curriculum. McGill Journal of Education (Online), 51(2), 833-856.

https://mje.mcgill.ca/article/view/9260/7123

Durksen, T. L., & Klassen, R. M. (2018). The development of a situational judgement test of personal attributes for quality teaching in rural and remote Australia. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(2), 255-276. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-017-0248-5

Fransson, G., Gallant, A., & Shanks, R. (2018). Human elements and the pragmatic approach in the Australian, Scottish and Swedish standards for newly qualified teachers. Journal of Educational Change, 19(2), 243-267. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-018-9321-8

Fraser, P. (2017). The OECD Diffusion Mechanisms and its Link with Teacher Policy Worldwide ☆. In C. Smith William (Ed.), The Impact of the OECD on Education Worldwide (Vol. 31, pp. 157-180). Emerald Publishing Limited.

Fullan, M., Rincón-Gallardo, S., & Hargreaves, A. (2015). Professional Capital as Accountability. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 23(15), 1-22. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/docview/1720064703?accountid=14543

Gitomer, D. H. (2019). Evaluating instructional quality. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 68-78. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1539016

Gore, J. M. (2021). The quest for better teaching. Oxford Review of Education, 47(1), 45-60. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1842182

Hartong, S., & Nikolai, R. (2017). Observing the “Local Globalness” of Policy Transfer in Education. Comparative Education Review, 61(3), 519-537. Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com.libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/docview/1941338056?accountid=14543

König, J., & Pflanzl, B. (2016). Is teacher knowledge associated with performance? On the relationship between teachers’ general pedagogical knowledge and instructional quality. European Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4), 419-436.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2016.1214128

La Velle, L., & Flores, M. A. (2018). Perspectives on evidence-based knowledge for teachers: acquisition, mobilisation and utilisation. Journal of Education for Teaching, 44(5), 524-538. https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2018.1516345

Lee, S. W. (2018). Pulling Back the Curtain: Revealing the Cumulative Importance of High-Performing, Highly Qualified Teachers on Students’ Educational Outcome. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 40(3), 359-381.

https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373718769379

Lingard, B., & Lewis, S. (2017). Placing PISA and PISA for Schools in Two Federalisms, Australia and the USA. Critical Studies in Education, 58(3), 266-279.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2017.1316295

Lubienski, C. (2018). The Critical Challenge: Policy Networks and Market Models for Education. Policy Futures in Education, 16(2), 156-168.

https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210317751275

Martínez, J. F., Schweig, J., & Goldschmidt, P. (2016). Approaches for Combining Multiple Measures of Teacher Performance: Reliability, Validity, and Implications for Evaluation Policy. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 38(4), 738-756.

http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0162373716666166

McNally, S., & Slutsky, R. (2018). Teacher–child relationships make all the difference: constructing quality interactions in early childhood settings. Early Child Development and Care, 188(5), 508-523.

https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1417854

Mockler, N. (2018). Discourses of teacher quality in the Australian print media 2014–2017: a corpus-assisted analysis. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1553849

Mockler, N., & Stacey, M. (2021). Evidence of teaching practice in an age of accountability: when what can be counted isn’t all that counts. Oxford Review of Education, 47(2), 170-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2020.1822794

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., and the Prisma Group. (2009). Reprint—Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Physical Therapy, 89(9), 873-880. https://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/89.9.873

Murgatroyd, S., & Sahlberg, P. (2016). The Two Solitudes of Educational Policy and the Challenge of Development. Journal of Learning for Development, 3(3), 9-21.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1120308.pdf

Nordin, A., & Wahlström, N. (2019). Transnational policy discourses on ‘teacher quality’: An educational connoisseurship and criticism approach. Policy Futures in Education, 17(3), 438-454. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318819200

Paugh, P., Wendell, K. B., Power, C., & Gilbert, M. (2018). ‘It’s Not That Easy to Solve’: edTPA and Preservice Teacher Learning. Teaching Education, 29(2), 147-164.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2017.1369025

Pickering, C., & Byrne, J. (2013). The benefits of publishing systematic quantitative literature reviews for PhD candidates and other early-career researchers. Higher Education Research & Development, 33(3), 534-548.

https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841651

Reid, J.-A. (2019). What’s good enough? Teacher education and the practice challenge. The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(5), 715-734. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00348-w

Ronksley-Pavia, M., Barton, G. M., & Pendergast, D. (2019). Multiage education: An exploration of advantages and disadvantages through a systematic review of the literature. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 44(5), 23-41.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1217916.pdf

Rowe, E. E., & Skourdoumbis, A. (2019). Calling for ‘urgent national action to improve the quality of initial teacher education’: the reification of evidence and accountability in reform agendas. Journal of Education Policy, 34(1), 44-60.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2017.1410577

Schleicher, A. (2016). Challenges for PISA. Relieve, 22(1), 1-7.

http://dx.doi.org/10.7203/relieve.22.1.8429

Scholes, L., Lampert, J., Burnett, B., Comber, B. M., Hoff, L., & Ferguson, A. (2017). The Politics of Quality Teacher Discourses: Implications for Pre-Service Teachers in High Poverty Schools. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 42(4), 19-43.

http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2017v42n4.3

Simmie, G. M., Moles, J., & O’Grady, E. (2019). Good teaching as a messy narrative of change within a policy ensemble of networks, superstructures and flows. Critical Studies in Education, 60(1), 55-72. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2016.1219960

Sinnema, C., Meyer, F., & Aitken, G. (2017). Capturing the complex, situated, and active nature of teaching through inquiry-oriented standards for teaching. Journal of Teacher Education, 68(1), 9-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487116668017

Skourdoumbis, A. (2017a). Assessing the productivity of schools through two “what works” inputs, teacher quality and teacher effectiveness. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 16(3), 205-217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-016-9210-y

Skourdoumbis, A. (2017b). Teacher Quality, Teacher Effectiveness and the Diminishing Returns of Current Education Policy Expressions. Journal for Critical Education Policy Studies, 15(1), 42-59. Retrieved from

http://search.proquest.com.libraryproxy.griffith.edu.au/docview/1913353006?accountid=14543

Skourdoumbis, A. (2019). Theorising teacher performance dispositions in an age of audit. British educational research journal, 45(1), 5-20. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3492

Spillman, D. (2017). A Share in the Future . . . Only for Those Who Become Like ‘Us’!: Challenging the ‘Standardisation’ Reform Approach to Indigenous Education in the Northern Territory. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 46(2), 137-147. http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/jie.2017.3

Steinberg, M. P., & Kraft, M. A. (2017). The Sensitivity of Teacher Performance Ratings to the Design of Teacher Evaluation Systems. Educational Researcher, 46(7), 378-396. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17726752

Steiner-Khamsi, G. (2016). New Directions in Policy Borrowing Research. Asia Pacific Education Review, 17(3), 381-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s12564-016-9442-9

Stolz, S. A. (2018). A Genealogical Analysis of the Concept of ‘Good’ Teaching: A Polemic. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 52(1), 144-162. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9752.12270

Tsai, C.-L., & Ku, H.-Y. (2020). Does teacher quality mean the same thing across teacher candidates, cooperating teachers, and university supervisors? Educational Studies, 47(6), 716-733. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2020.1729098

Wachen, J., Harrison, C., & Cohen-Vogel, L. (2018). Data Use as Instructional Reform: Exploring Educators’ Reports of Classroom Practice. Leadership and Policy in Schools, 17(2), 296-325. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2016.1278244

Zeichner, K., & Hollar, J. (2016). Developing professional capital in teaching through initial teacher education: comparing strategies in Alberta Canada and the U.S. Journal of Professional Capital and Community, 1(2). https://doi.org/10.1108/JPCC-01-2016-0001

Total views : 40037

Total views : 40037